I recently went to my local Barnes and Noble to “check out books.” It’s what I do – I’m a book love who loves the importance of reading. But going to the bookstore is a trap for me. That’s because no matter how hard I try, I always end up leaving with a book or two in my hands.

On this particular trip, this exact same scenario played out all over again. I went into the Barnes unequivocally telling myself, “I AM NOT GOING TO BUY ANYTHING!”

Lo and behold, I left with not one, but two books.

Why did I make this irrational decision to go to the bookstore knowing full well that I would spend my money like I have every single time? According to behavioral economics, we humans are irrational creatures. “Contrary to traditional theories of economics,” states an blog article by design consultancy Bridgeable, “[behavioral economics] says that people are irrational — meaning there is more to decision-making than simply providing accurate information and expecting people to act on it accordingly.

Businesses know full well that humans are irrational, and use this to their advantage. Take, for example, the notorious “Buy One Get One (BOGO)” deals. We all know that spending money doesn’t save us money, but our consumer decisions show that we behave in a way that is completely contrary to this fact.

And although it seems that behavioral economics can help more in aiding consumer consumption than in the design of visual projects, we cannot deny the fact that design is all about perception. How viewers perceive the world determines the action that they take. Behavioral economics, alongside other theories on perception, allows designers to create products and services that play into the cognitive biases of users.

Why Designers Should Care About Behavioral Economics

Although humans tend to think of themselves as rational decision makers, behavioral economics argues in favor of the opposite. Should a designer approach their creative process with an understanding of basic behavioral economic principles, they will be able to better guide the user. After all, solving a user’s problems starts by understanding who they are – including, to an extent, their psychological behaviors.

From the onset, the connection between behavioral economics and design seems rather hazy. But a further understanding of behavioral economics demonstrates how they complement each other – to solve problems, we have to understand how people, well, solve problems, and that is in irrational ways.

The field of public health – one distant from the design industry – also uses an understanding of behavioral economics to its benefit. According to an article by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, “Human beings act irrationally. This long-established observation, corroborated now by the burgeoning field of behavioral economics… holds great potential to transform both personal habits and public health.” If health experts are taking note of human behavior, designers – those who design products and services to be used by people – should sit up and listen as well.

“It’s not news to designers that people don’t always behave as self-reported,” states the Bridgeable article. “Understanding this is fundamental to our practice of uncovering insights through primary research and testing our designs by having users interact with prototypes.”

If designers know from the onset that humans won’t behave like they think they will, the designer can create a more effective product which more accurately caters to user behavior.

But Is This Even Ethical?

When designers use behavioral economics to their benefit, they need to have a mindset of a storyteller who guides the user to the intended action. Any touchpoint on the user journey should get them to the finish line – and it is the duty of the design to get the user across.

Taking the knowledge that humans don’t act rationally, designers can lean into this flaw. Designers can form what the user perceives, leading them to make their final decision. For example, on a website, designers should limit obstacles to purchasing products as to eliminate friction. This leans into the behavioral economic principles of friction costs and defaulting, as discussed by Bridgeable. The former argues that obstacles scare people away, while the later suggests that humans avoid the hard paths. Designers should make things as easy as possible – or, “add small barriers to hinder undesirable behaviour.”

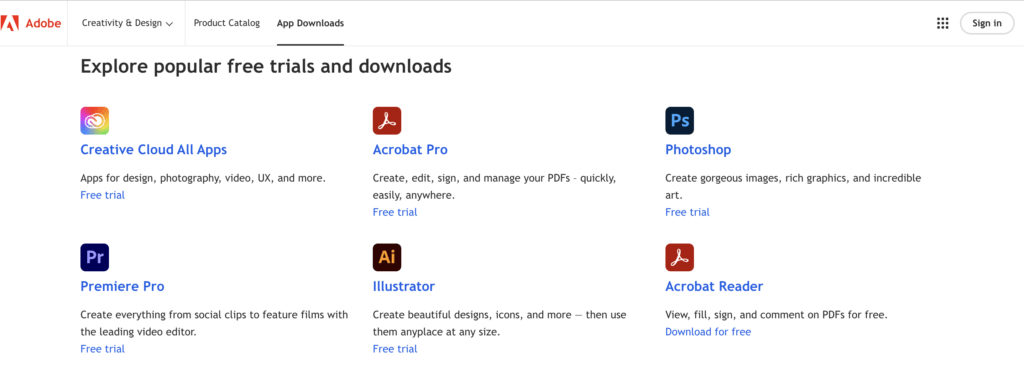

Think back to the BOGO example I gave earlier. According to an article by Samantha Hops for digital marketing agency Digivate, “consumers will get a lovely hit of dopamine when they see the word ‘Free’, and that will be reinforced when they take advantage of that offer.” In this context, Hops was writing about free trials – but the same goes for the BOGO example. When I see free, I immediately think I am getting the upper hand, when I am actually getting played in reality. As the old adage goes, ‘there’s no such thing as a free lunch.”

Hops uses Adobe as an example of the free trial. Adobe constantly provides free trials of their software. Free trials make us think that the company is being kind, and that we can get rid of the product later, without any payment, if we don’t link it.

But if we have our hearts set on not liking the product, why would we bother to get a free trial in the first place? The short answer is that it is an irrational behavior, backed by behavioral economic principles. “Customers new to Adobe can take out a 30-day free trial to see if the software works for them,” writes Hops, “which you’d think is a big loss-maker for the company – but it’s quite the opposite as people get used to using the software and don’t want to give it up.”

It seems to be a form of storytelling as much as it is a tale of customer manipulation. Now, the topic of whether using this knowledge of behavioral economics is ethical is a long discussion; one beyond the scope of this article. On a personal level, I feel that implementing a behavioral economic framework into the design process can potentially open the door to unethical behaviors.

Others feel the same. “The ethical implications of attempting to change behaviour on a large scale need to be considered before they are enacted,” writes Hayley Geary, a student at the London School of Economics, in an article for The Freethink Tank. “Inappropriate uses of when, how, and what to nudge is causing public concern, which may limit the potential of these techniques even when applied correctly and in good faith.”

Ethical concerns, however, do not make it less true that humans behave in certain behaviors, and designers can and must cater their products to those user actions. There must be a fine line in the practice of storytelling, to ensure that designers are not knowingly deceiving or manipulating their users to exhibit certain actions based on flawed decision making. In Geary’s mind, “a collaborative effort between academics and practitioners is vital to ensure nudges are both ethical and successful.”

Behavioral Economics Works With Other Psychological Theories

Designers have a role in shaping user perception through various means. Much of this is psychological, which falls into the wheelhouse of the behavioral economics field. Yes, designers can use behavioral economics, but can also use other theories which can correlate – and even build upon – the cognitive mishaps and limits of humans.

Top-Down Processing

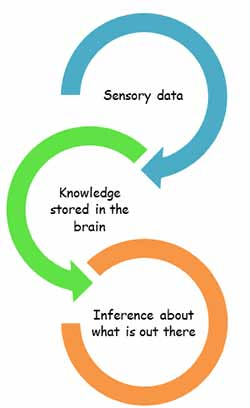

One such theory is top-down processing promoted by psychologist Richard Gregory. This psychological theory argues that humans perceive through contextual information coupled with prior knowledge. “Stimulus information from our environment is frequently ambiguous,” writes Dr. Saul McLeod in his article for Simply Psychology, “…so to interpret it, we require higher cognitive information either from past experiences or stored knowledge in order to make inferences about what we perceive.”

This psychological understanding plays into the concept of anchoring, the behavioral economic principle that previously presented knowledge will shape user decision-making in the future. For example, if the designer highlights a certain statistic on a website, and that is the first statistic the user sees, they will make decisions based on that statistic – even if other statements, including the seemingly contradictory ones, appear later. “The first fact, number, or figure a person hears will bias their judgements and decisions down the line” states the Bridgeable article.

Affordances

Another principle that works hand-in-hand with behavioral economics is the concept of affordances in design. Affordances are cues within the design that provide the possibility for a user interaction. According to Don Norman in a video provided in an Interaction Design Foundation article, “Affordances represent the possibilities in the world for how the agent (a person, animal, or machine) can interact with something.”

For example, a big red button on a website that proudly says “BUY NOW!” presents the opportunity for a user to interact with the site. This affordance also reduces the amount of friction needed for the user to take the desired outcome, which plays into the behavioral economic understanding of removing obstacles from the user path. It also relates to the understanding of touchpoints as places along the user journey, which designers can steer as the storyteller through behavioral economic principles.

Gestalt Theory

The most famous of theories presented in this article, however, is Gestalt theory. In a nutshell, humans like to simplify the complex, so we do this consistently with visuals. “According to the Gestalt principle of simplicity, the brain groups elements in order to minimize the number of objects in a scene,” writes designer Ellen Lupton in her book, Design is Storytelling.

And although there is no clear correlation between Gestalt principles and behavioral economics, it can be argued that humans like simplicity in general. BOGO is a simple offer to take advantage of, no matter how irrational it may be. But even more so is what Bridgeable deems the behavioral economic principle of the “Ostrich Effect,” where users tend to avoid warnings. As irrational as it is, people don’t want to look back to see what they did wrong. Introspection is scary. And so in order to counter this, we must guide people through more simple nudges. That old K.I.S.S. acronym – “keep it simple, stupid” – as is truthful as it is hurtful.

Proceed With Caution

Knowing user behavior allows designers to cater products and services to work to their own advantage. Behavior economics, although a psychological field, plays into other theories as they relate to perception; most of them already used in the design field. Designers should incorporate behavioral economic principles to work hand-in-hand with other well-established frameworks – but should be warned in doing so.

Ethically, there is nothing that says we shouldn’t guide users to the solution. But it shouldn’t be misleading, either. In her book’s section on behavioral economics, Ellen Lupton warns that “Designers should proceed with caution when applying insights from behavioral economics and other fields of psychology… Like doctors, designers should pledge to do no harm and use the amazing power of language and design to advance the common good.”

Behavior economics, like other theories, is a tool that designers can use to shape perception. It can allow designers to create products and services that get businesses to their intended goals, and even create ROI. But using behavioral economics should be done carefully – strategically, even – and with only the best of intentions. That being said, designers should not be scared of these basic principles, and a surface-level understanding of behavioral economics can allow designers to create more effective solutions to solve user needs and problems.

Citations

Geary, H. (2019, October 17). To nudge or not to nudge: The ethical debate within behavioural economics. The Freethink Tank. https://www.thefreethinktank.com/nudge-ethical-debate-behavioural-economics/

Harvard University. (2013). Q&A: The Science of Irrationality. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/magazine/qa-the-science-of-irrationality/

Hops, S. (20AD). 9 eye-opening examples of behavioural economics marketing. Digivate. https://www.digivate.com/blog/digital-marketing/behavioural-economics-marketing/

Interaction Design Foundation. (2024, June 5). What are affordances?. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/affordances

Lupton, E. (2017). Design is storytelling. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

McLeod, S. (2023, June 16). Visual perception theory in psychology. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/perception-theories.html

The top 5 behavioural economics principles for designers. Bridgeable. (n.d.). https://www.bridgeable.com/ideas/the-top-5-behavioural-economics-principles-for-designers/

Leave a comment