If you’ve ever bought an Apple product, you must be familiar with the sleek white boxes in which their gadgets arrive. Opening the box is a whole experience – you have to lift the lid, which slowly detaches from the box’s bottom, then remove the paper which proudly states “Designed in California,” to reveal the beautiful i-whatever you purchased.

Opening your Apple product for the first time is a whole experience; one that has been deemed by the broader internet community as “unboxing.” Brands use the box in which their product arrives as a consumer touchpoint. There is excitement in the customer when opening their newly-arrived product for the first time, as surprises often appear along the way. It is an immersive experience consisting of cardboard.

Immersive experiences are nothing new. They’ve existed long before the rise of AR and VR, and have been used by companies to generate an emotional response from their customers. DisneyWorld creates highly passionate emotions in “Disney Adults” who feel a deep passion for the brand. Everything from the designs of the parks, the smells that are intentionally released, and the “magic” at any and every consumer touchpoint invoke a plethora of emotions in their visitors. Being from the Northeast myself, I’ve seen an immersive experience in play at the local supermarket. Stew Leonard’s is a Norwalk, Connecticut based chain known for their singing animatronic animal displays. Seeing a bunch of pigs sing a catchy tune is a special experience, and one which a person won’t find at Kroger. It makes Stew Leonard’s different, recognizable, and albeit special – to the point where people feel excited to go to a supermarket.

People love experiences. In 1998, Harvard Business Review authors B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore proudly proclaimed that society was heading into the experience economy. “Today we can identify and describe this fourth economic offering” they wrote, “because consumers unquestionably desire experiences, and more and more businesses are responding by explicitly designing and promoting them.” Having a nice store or a good product alone is not enough: there must be an engaging experience that ignites an emotional connection with the customer.

The experience economy makes it all the more important for designers to understand how to create emotion-inducing products. Yes, a product should work, but function alone doesn’t make an impression. Adding an emotional aspect to the design makes it all the more powerful in resonating with product users. When designer’s bring users on an emotional journey, they create an immersive experience that makes their product all the more better.

Emotions Mix Like Paint

The backbone of a strong user experience are the emotions that are generated as a result of the interaction. Emotions have the ability to create bonds between the user and the product – so much so that they lead to brand loyalty and a deeper connection to the design. “Products that people love are products that people use over and over again,” according to the Interaction Design Foundation. “The corner stone of emotional design is the idea that if you can elicit strong emotions in your users – you can use those emotions to either create loyalty or to drive a customer to take action.”

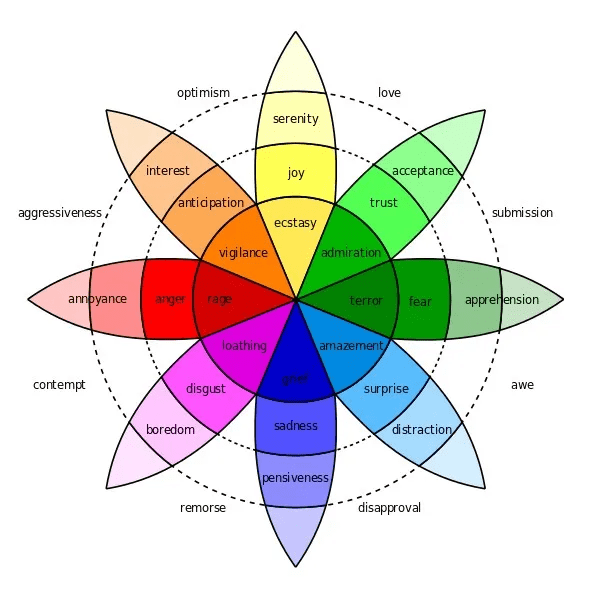

Robert Plutchik is credited for his Psycho-Evolutionary Theory of Emotion. He argued for eight basic emotions that can be broken down into four different emotional pairs. The Interaction Design Foundation suggests that in Plutchik’s theory, emotions can be mixed like paint, with “the idea being that blending different emotions will create different levels of emotion and response.”

Although Plutchik’s theory can be seen as being simplistic, its argument is essential for visual designers. Understanding user emotions can allow designers to better understand how to design products that resonate in the way they see fit. And if they can hit that emotion right on the head, it can lead to a user’s loyalty with the product or business.

An Emotional Roller Coaster

If Plutchik’s contribution to the study of emotion simplifies our understanding of how they can be categorized, Don Norman and Andre Ortony can be credited in furthering the understanding of how users respond with those same emotions. Norman and Ortony break down emotional responses to the reactive, behavioral, and reflective levels – each building on the next.

Reactive responses deal with the emotions that appear at face value. Then, the user reaches the behavioral level, where emotions appear based on their experience in using the product. Finally, the highest level is the reflective level, which calls for a deep reflection. Arguably, this is the stage in which the strongest bonds are formed. According to Norman and Ortony, a visual designer being proud of their work is a form of a reflective level response. “It is the only level at which fullfledged emotions can arise,” write Norman and Ortony, “that is, emotions that incorporate a sense of feeling derived from the affective components from the Visceral and Behavioral levels, along with a conscious interpretation of that feeling.”

Regardless of whether or not the designer is attempting to evoke a certain emotion, a user’s experience with a product will result in certain emotions – which is all the more reason for the creator to care about emotional design. If the designer is trying to create a positive experience for the user, they would seek to eliminate any possibility for the product to evoke a negative emotion; a practice dubbed by Norman and Ortony as emotion-prevention, or emotion by design. “Almost any design stance that minimizes utilitarian difficulties,” they write, “also serves to reduce negative emotions by reducing the undesirable effects that lead to them.”

But, alas, no designer is perfect. Their design might land the user on the negative side of Plutchik’s wheel, resulting in emotions the designer might rather avoid. “Emotional affordances can arise by accident or by design, although they are more likely to arise by accident when designers focus on utility, and by design when they focus on appearance.” The result of the utilitarian focus, in contrast to emotion by design, is emotion by accident.

Visual designers should not only focus on blending different emotions to create strong bonds with the user – they must also work to ensure that their design evokes the emotions they seek. Otherwise, they are only performing a disservice to themselves – and quite possibly, the users and the business served.

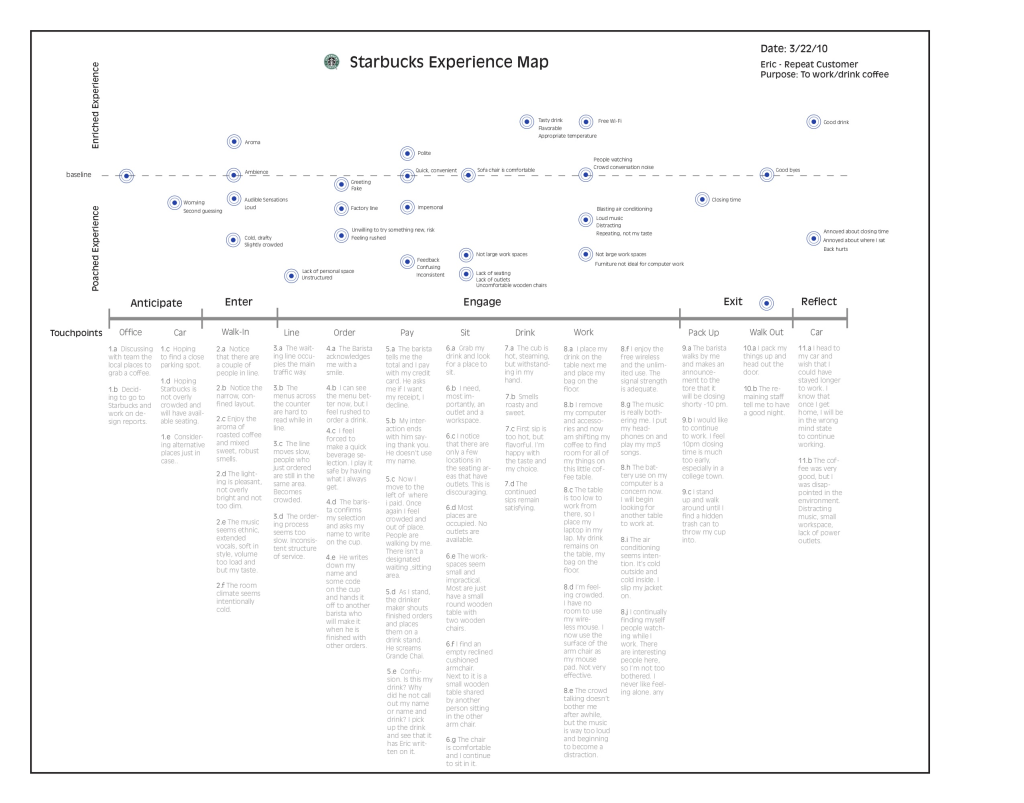

It is no wonder, then, that larger brands such as Starbucks map out their customer’s journey at every touchpoint to ensure the desired emotional response. According to an article by customer service company Local Measure, a well-planned customer journey map leaders to excellent customer service experiences. “Behind these exceptional customer experiences sits a carefully architected customer journey map,” they proudly claim, showcasing the Starbucks model which highlights the customer’s emotion at every stage of interaction within and outside of the cafe.

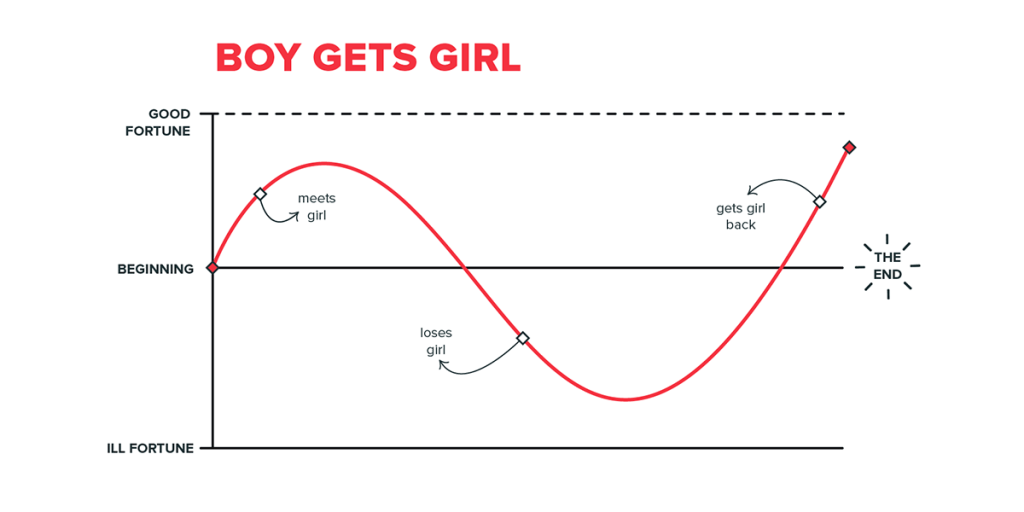

Remarkably, the customer journey map is highly reflective of a model used in fiction. The famed author Kurt Vonnegut proposed his emotional journey framework as his college thesis – a seemingly excellent argument that ended up being denied. Nonetheless, time has proved Vonnegut to be correct. In her book Design is Storytelling, Ellen Lupton, chair of the graphic design program at the Maryland Institute College of Art, wrote that “he argued that all stories can be mapped as a line moving up and down between misery and ecstasy.” The similarity between Vonnegut’s simplistic approach and Starbucks’ complicated map is highly noticeable. Lupton would most likely agree, noting in her book that “designers create emotional journey maps analogous to Vonnegut’s graphs… Some steps in the journey are positive, while others are negative.”

In the grand scheme of storytelling, the designer is ultimately the guide. The visual designer maps out the user journey, and aims to create a product that only results in bringing out the correct emotions in the user. There are ups and downs, highs and lows along the user journey and it is the duty of the designer to get it just right.

The Tools You Need

Thankfully, there are many tools available to visual designers that allow them to do exactly that. One of these tools is the persona, which they can create to understand a specific user of their product. According to Aurora Harvey in an article for the Nielsen Norman Group (notably established by the same Don Norman mentioned in this article), a persona is a “fictional, yet realistic, description of a typical or target user of the product.” Understanding potential users and their issues can allow designers to create products that lead to positive experiences and grow that strong emotional bond. If the visual designer is well-informed about their audience, they can make the necessary decisions in the design process which could lead to the intended emotional response from the user.

Once the users are fully understood, designers must effectively incorporate the use of color, typography, and graphics in addition to the utilitarian necessities of the design. Color psychology helps in regard to understanding how different colors are associated with different emotions. As defined in an article by Céillie Clark-Keane, “Color psychology is the theory that certain colors elicit a physical or emotional reaction and, in doing so, shape human behavior.” So be warned: to choose the wrong color is to share the wrong message. It’s so important that Clark-Keane goes as far as to suggest running user tests just for color alone.

According to an article by Jerry Cao about choosing colors when designing a website, “No matter what colors you choose, they have a definite influence on the design as a whole — from communicating contrast or similarity, to evoking precise emotions.” With this understanding, designers can implement Norman and Ortnoy’s practice of emotion by design to either incorporate or avoid the use of certain colors. Ellen Lupton notes the connection of color to evoking emotions, using the examples of red and green. Want to communicate passion and romance? Use red. Want to make salty chips somehow seem healthier? Use green. It works like magic.

The same methodology can be used when it comes to the choice of typefaces. It is no secret to graphic designers that typography can make or break the emotional effectiveness of a design. Sophia Bernazzani, in an article for HubSpot, makes a brief comment about cognitive fluency. In short, hard to read instructions automatically communicates to the reader that the instructions are hard to do – even if that may not be the case. “This is an example of cognitive fluency,” writes Bernazzani, “a theory that posits when our brains have difficulty processing information, the task at hand appear more challenging.” This type of hardship would arguably evoke a negative emotion in the reader – one that any writer, or designer, would seek to avoid. Typefaces, in and of themselves, have the ability to convey certain messages in the same psychological way which colors powerfully do. Or, as Grace Fussell puts it in her article for Envato, “designers can manipulate the psychological responses of their viewers by making informed choices about the features of a design, such as colors and fonts.”

If colors and typefaces alone weren’t enough for the visual designer to work with, they must also consider imagery and graphics. Emojis are a case in point– they have the ability to communicate stories in a simple way, and can also convey emotion while doing so. Adam Bloomberg notes how emojis can even be used in a court of law to depict the case. “Much like people in the present day frequently communicate with only pictures,” writes Bloomberg, “you can use icon-heavy graphics to walk [the jury] through unfamiliar or complex concepts. Flowcharts can be the perfect place to take this approach.” If graphics can serve as a powerful aid in a legal proceeding to make ideas more relatable and simplistic, how much more powerful can they be in emotional design? It can evoke a positive experience, leading to a strong bond.

All of these tools engage the five senses, allowing for the user to truly have an immersive experience with the design. The effective visual designer is able to stimulate the senses to garner the intended emotional response. They thereby heed the tip given by Pine II and Gilmore in the Harvard Business Review article I mentioned earlier: “Engage all five senses.” Beyond just visceral reactions, the tools, when used as intended, can lead to powerful behavioral and even reflective responses.

Emotions are Valuable

There are many emotions that a visual design can evoke – and different levels in which a user can emotionally respond. When a designer understands their user and is able to chart an emotional journey, they can cater their design to the user’s senses. This powerful and intellectual exploration can therefore result in the intended emotions by design, creating the strong bonds sought after in the experience economy.

Experiences create emotions that create loyal customers. It’s why brands turn their boxes into an entertaining venture, why Disney powerfully tells inspiring stories, and why Stew Leonard’s is just a fun supermarket to be at. Emotions lead consumers to make certain decisions, whether it be logically or psychologically.

Emotions are valuable to the field of visual design, because designers create products for people. And if people have a positive experience with the product, the designer will have solved the user’s problem. Without a thorough understanding of the user, the designer will not evoke the intended response through their creation.

So before you go about designing anything, return to the head of design – solving a problem for the user. And if you can make the user happy while doing so, you will have done your job while creating a new customer.

Citations

Barron, S. B. (2016, December 14). Fonts & Feelings: Does Typography Connote Emotions?. HubSpot Blog. https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/typography-emotions

Bloomberg, A. (2019). Storytelling in the age of emojis. US Law, 28–30.

Cao, J. (2015, April 7). Web design color theory: How to create the right emotions with color in web design. TNW | Tnw. https://thenextweb.com/news/how-to-create-the-right-emotions-with-color-in-web-design

Clark-Keane, C. (2024, February 26). 8 ways to use color psychology in marketing (with examples) | wordstream. WordStream by LocaliQ. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2022/07/12/color-psychology-marketing

Column Five. (n.d.). Kurt Vonnegut visualizes the most popular stories of our civilization. https://www.columnfivemedia.com/kurt-vonnegut-visualizes-stories-civilization/

Fussell, G. (2024, February 16). The psychology of fonts: How to choose fonts that evoke emotion. Envato. https://elements.envato.com/learn/the-psychology-of-fonts-fonts-that-evoke-emotion

Harley, A. (2015, February 16). Personas make users memorable for product team members. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/persona/

Interaction Design Foundation. (n.d.). Putting some emotion into your design – plutchik’s wheel of emotions. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/putting-some-emotion-into-your-design-plutchik-s-wheel-of-emotions

Local Measure. (19AD). Mapping the emotional customer journey. Local Measure. https://www.localmeasure.com/post/mapping-the-emotional-customer-journey

Lupton, E. (2021). Design is storytelling. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Norman, D., & Ortony, A. (2006, January). Designers and users: Two perspectives on emotion and design.

Pine II, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (2014, August 1). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1998/07/welcome-to-the-experience-economy

Leave a comment